Electric cars evolved from elite transport in the 1900s to Ford’s Model T revolution. GM’s 1996 EV1 met emissions standards but was controversially scrapped in 2005. Tesla now leads, yet its future hinges on shifting US policies, reflecting a century of innovation, setbacks, and environmental activism.

Introduction

Transition to electric cars represents a key component of a global strategy to fight and mitigate climate change and global warming. Governments worldwide, including the prior Democratic administration in the United States, have established ambitious targets for electric car adoption. Currently, China has a significant lead in electric car ownership, followed by several European nations. In the US, Tesla, under the leadership of Elon Musk, has become synonymous with electric cars, although established automotive manufacturers such as Ford and General Motors have also invested heavily and are also producing electric models.

Despite these initiatives, adoption of electric vehicles has been slow, particularly in the US. The escalating frequency of extreme weather events, such as the 2024 wildfires in Los Angeles and hurricanes in North Carolina, underscores the urgency of this transition. This situation prompts a natural question: could the widespread adoption of electric vehicles have occurred significantly earlier? Given the longstanding availability of core EV components, such as batteries and electric motors, could widespread implementation have been realized decades prior?

This article will demonstrate that, with a few different favorable circumstances at certain historical junctures, widespread adoption of electric cars could have been achieved years ago. For instance, the collaborative efforts of Thomas Edison and Henry Ford held the potential to give a boost to electric cars production in the early twentieth century; however, their efforts, although promising, did not quite produce the desired result. Similarly, in the 1990s, General Motors, in response to California’s stringent emission standards, produced an electric car, EV1, that was received with considerable enthusiasm by its initial users; however, General Motors abruptly terminated the project, as captured in the documentary “Who Killed the Electric Car?”. While General Motors must have faced challenges similar to those confronting current electric car adoption, such as insufficient charging infrastructure, battery limitations, and competition from gasoline cars, these obstacles could have been overcome through sustained commitment from governments and automotive manufacturers. Had the current transition commenced in the 1990s, the progress toward widespread electric car adoption would likely be significantly more advanced than it is today. This earlier transition might have been sufficient to avert the most severe impacts of global warming.

The Late 1800s and Early 1900s: A Promising Start

History of electric cars stretches back nearly 200 years [1] [2] [3]. They predate widespread use of internal combustion engine (ICE) or gasoline cars. Some rudimentary electric cars were developed in the early 1800s, but more serious efforts started later that century after rechargeable batteries came along in 1859. Philadelphians Pedro Salmon and Henry G. Morris got the first patent for a commercially viable electric car in 1894. Based on a version of this car, a new company, the Electric Vehicle Company (EVC), was incorporated in New Jersey which started attracting wealthy investors. By the early 1900s, this company had more than 600 electric cabs operating in New York with smaller numbers in Boston and Baltimore. In New York, an ice arena was converted into a battery swapping station; a cab could drive in there, get the used battery replaced by a new battery, and drive out within just a few minutes. Things worked really well for a few years, but then unforeseen conflicts emerged among investors and partners, and the company collapsed in 1907.

At the turn of the century (early 1900s), electric cars were gaining popularity in major cities across the United States and Europe. They were quiet, easy to drive, and didn’t emit smelly pollutants. Compared to their internal combustion engine (ICE) counterparts, which required manual cranking and gear shifting, electric cars were relatively simple to operate. Electric cars offered a smoother and quieter ride, making them appealing to urban dwellers. The limited range of early ICE vehicles and the lack of widespread gasoline infrastructure made electric cars a practical choice for short-distance urban travel. As a result, electric cars outsold gasoline-powered cars in the early 1900s, with notable manufacturers like Baker Electric, Columbia Electric, and Detroit Electric producing a variety of models for personal and commercial use. Detroit Electric cars, produced by the Anderson Electric Car Company in Detroit, Michigan, built 13,000 electric cars from 1907 to 1939. Clara Ford, Henry Ford’s wife, apparently preferred Detroit Electric cars over her husband’s noisy and dirty gasoline cars.

One fascinating chapter during this period in the history of electric cars involves the collaboration of Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, two of America’s greatest inventors and entrepreneurs [4]. Edison, a strong advocate for electric cars, worked for many years on improving battery technology. Ford, while working for Edison at Edison’s company, developed plans for his Model T gasoline car (released in 1908). While Edison encouraged Ford’s Model T pursuits, he continued his battery research, eventually supplying his nickel-iron batteries for various applications, including existing electric cars.

In 1914, newspapers reported on a planned Ford-Edison electric car, utilizing a Model T chassis. For example, the New York Times, in their January 11, 1914 issue, quoted Ford as saying, “Within a year, I hope, we shall begin the manufacture of an electric automobile. The fact is that Mr. Edison and I have been working for some years on an electric automobile which would be cheap and practicable.”

However, the project stalled when Ford insisted on using Edison’s nickel-iron batteries, which unfortunately were not yet completely ready for electric cars. Engineers at Ford secretly used lead-acid batteries in the prototype; when Ford came to know that, he was enraged and he cancelled the project right away. Ford’s decision might have been influenced by other factors like cost, profitability and market for electric cars, but there is no public record of that.

Dominance of electric cars in the early 1900s was, however, short-lived. The Ford Model T, introduced in 1908 with its assembly line production starting in 1913, significantly reduced the cost of gasoline-powered cars, making them more accessible to the average consumer. Furthermore, the discovery of vast oil reserves and the development of a nationwide gasoline infrastructure further cemented the dominance of ICE vehicles. The Ford Model T was far more affordable, and the advent of the electric starter did away with the hand-crank problem for gasoline cars. By the 1930s, electric cars had largely disappeared from the market, unable to compete with the affordability, range, and convenience of gasoline-powered cars. The electric car industry entered a period of decline that would last for several decades.

Renewed Interest and Challenges – California ZEV mandate (late 1900s)

Interest in electric cars briefly resurfaced in the late 1960s and early 1970s due to soaring gasoline prices and gasoline shortages; but that did not last long as gasoline prices stabilized. However, the situation changed again in the 1990s with new federal and state regulations.

In 1990, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) enacted the Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandate, stating that the seven leading automakers marketing vehicles in California must produce and sell zero-emissions vehicles to maintain access to the California market. The mandate required a percentage of new cars sold in California to have zero emission; the percentage increased from 2% in 1998 to 10% in 2003.

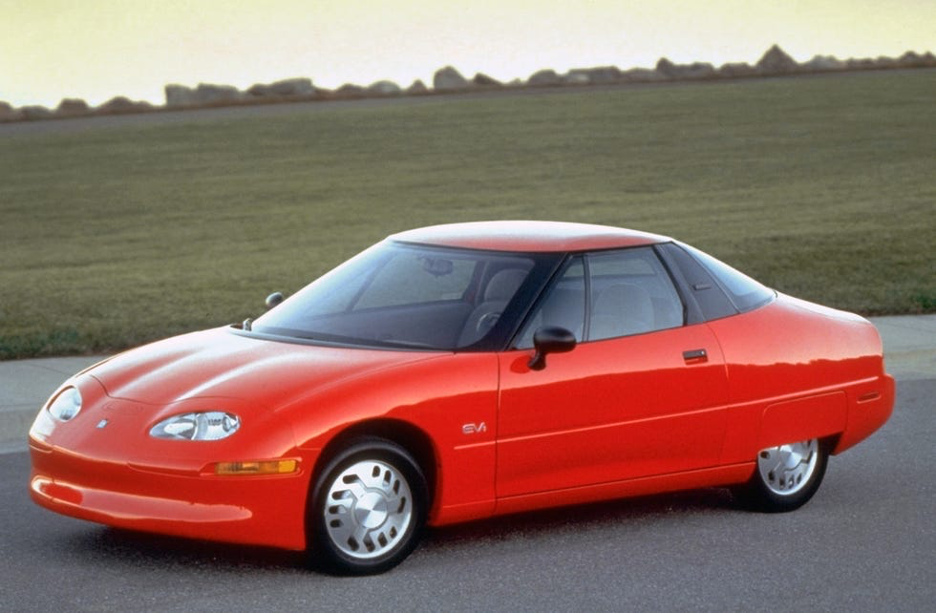

The California mandate spurred many of the car companies to devote serious efforts and resources to produce an electric car. GM’s EV1, a purpose-built electric car, based on their prototype car called “Impact”, was a standout [5]. Designed from the beginning for mass production, it was a sleek, futuristic-looking coupe (Figure 1) with a powerful electric motor and advanced features like regenerative braking, keyless entry, and low-rolling-resistance tires; these features have become commonplace in today’s electric cars. The first generation EV1 used lead-acid batteries; but later models featured nickel-metal hydride batteries, extending the range to 75-140 miles. GM produced a total of 1117 EV1s and the cars were only leased to customers.

Figure 1. GM EV1 Photo – CARandDRIVER Magazine [6].

The EV1users loved the car for its performance, smooth ride, and quiet operation. Many lessees became enthusiastic EV1 advocates, impressed by the car’s technology and its environmental benefits. However, even though there were many happy customers, GM abruptly canceled the EV1 program in 1999. All the leased cars were recalled and, with a few exceptions, they were all crushed and destroyed. This decision, documented in the film “Who Killed the Electric Car?” [7], sparked outrage among EV enthusiasts and lessees, who felt that GM had prematurely abandoned and deliberately suppressed electric car technology.

GM cited various reasons for discontinuing the EV1, including high production costs, limited market demand and the lack of a robust charging infrastructure.

While GM’s concerns about the electric car market may have been real, all of those could possibly be mitigated over time by serious commitment from the government and the car manufacturers.

Some of the other manufacturers had converted their existing gasoline cars to electric cars to meet the demands of the ZEV mandate. But they also followed GM’s lead, repossessed their electric cars, and in many cases, crushed and destroyed them

If GM’s EV1 program had continued and other car companies followed suite, the USA and the world could be almost 10-15 years ahead in the race to transition to electric cars and that would make a huge difference in the global fight toward reducing pollution and global warming!

Modern Era – The Rise of Tesla

Despite earlier promise, widespread electric car adoption didn’t occur until the 21st century. Two California engineers and entrepreneurs, Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning, both concerned about worsening pollution, test-drove a concept electric car Tzero produced by a small company called AC Propulsion. They liked the car and wanted its owner to put this car for commercial production. When AC Propulsion refused, Eberhard and Tarpenning founded Tesla Motors in 2003 and decided to produce their first car based on the Tzero. Elon Musk joined soon after, investing and leading the design of the Tesla Roadster, the new name for the car. The Roadster, launched in 2008, was a high-performance sports car with impressive range and acceleration, a significant advancement over previous electric cars.

Beyond the Roadster, Tesla has of course gone ahead to produce a number of different models to meet the needs of different segments of consumers. While other manufacturers now produce electric cars, Tesla holds a dominant market share in the US. In 2024, US EV sales reached 1.3 million, representing about 8% of all car sales. Advances in lithium-ion battery technology significantly improved range and performance, addressing a key limitation of earlier electric cars. However, in spite of excellent progress, growth slowed in 2024, and the US lags significantly behind China and many European countries, where electric car adoption rates are much higher. Preference for hybrid and plug-in hybrid cars in the US also contributes to the slowdown in pure electric car sales, with sum total of all these cars accounting for nearly 25% of all car sales in 2024 in the US.

Evolution of Battery Technology

Battery is by far the most important component of an electric car as the battery determines every aspect of an electric car’s performance like range, pickup and maximum speed. So, advancement or lack of it of battery technology has been a key factor in holding back progress in adoption of electric cars. Although Volta is credited for the invention of the first battery as early as the year 1800, the first rechargeable battery which is needed for electric cars was invented by Gaston Plante, a French physicist, in 1859. This was a lead-acid cell consisting of a lead anode and a lead dioxide cathode immersed in sulfuric acid. These lead-acid batteries tend to be heavy and are still used in many applications, including in all gasoline cars, where weight is not that much of an issue.

Thomas Edison started working on batteries in the 1890s and his goal was to produce a lightweight and durable battery that could be used in electric cars and hence push forward adoption of electric cars. He patented an alkaline-based nickel-iron battery in 1901. It took him several years to improve the battery so that it would be suitable for use in electric cars. Edison’s battery eventually achieved good success in many applications, including electric cars, but he lost the race to Ford Model T gasoline car which rapidly started gaining in popularity.

Over the years, batteries went through different iterations like nickel-cadmium batteries, nickel-hydrogen battery; but fast forward to 1985, a Japanese team first developed the lithium-ion battery, a rechargeable and more stable version of previous lithium batteries. Sony commercialized the lithium-ion battery in 1991 and these have been the batteries of choice for most electric cars to date.

The next big development was the solid-state battery in 2024; these batteries use solid electrolytes and are safer, more durable and perform better. Electric cars are likely to use these in the coming years.

Government Policies and the Future of Electric Cars

US electric car production and sales have been heavily influenced by government policies, including the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, enacted by the former Democratic president, Joe Biden. These initiatives provided funding for charging infrastructure, manufacturer loans, and consumer rebates. In addition, the US government had provided significant loans to Tesla in its early years to push forward production of electric cars. The Biden administration’s push for increased zero-emission vehicle sales, aiming for 50% electric car sales by 2030, has however been challenged by the current Republican administration [8]

. Continuation of government support and incentives remains very uncertain. These policy shifts will very likely slow down the transition to electric cars, at least in the US, but many believe that the eventual transition to electric car is now unstoppable, driven by a growing worldwide market for these cars.

Summary and Conclusion

Electric cars have existed in diverse forms over the past two centuries. While widespread availability of electric cars was not realized until the 21st century, historical junctures existed where, with more favorable circumstances, electric cars could have achieved a more dominant position in transportation much earlier. The first such juncture was the collaborative endeavor between Henry Ford and Thomas Edison around 1914. Had Edison’s nickel-iron batteries, subsequently utilized in electric cars, been available for the Ford-Edison prototype, adoption of electric cars could have received a boost, however short-lived that might be. A subsequent pivotal moment was the production of General Motors’ EV1 vehicles in the late 1990s. Although these vehicles garnered considerable acclaim from lessees and drivers, GM abruptly decided to cancel the whole program, recalled all the leased cars and destroyed them. Had GM continued the EV1 program and capitalized on its initial success, that could have resulted in gradual adoption of electric cars approximately 10 to 15 years prior to the widespread availability of Tesla vehicles.

Currently, all the requisite elements for a comprehensive transition to electric cars are in place; however, sustained governmental commitment is still imperative to achieve widespread adoption. The US automotive manufacturers have made substantial financial investments in the production of electric cars and the advancement of battery technology, driven by the need to compete in the expanding global market. Nevertheless, the US government must maintain its support for the development of charging infrastructure and the provision of consumer tax rebates for electric car purchases. It is in the national interest of the United States to promote the adoption of electric cars, thereby mitigating pollution, reducing global warming, and averting the associated catastrophic natural disasters. Should the United States government discontinue the incentives for electric car adoption initiated during the Biden administration, that will be a significant blow to the transition to electric cars. The eventual transition to electric cars will still occur, but the pace of adoption may not be sufficient to prevent the worst effects of global warming.

References

- https://www.energy.gov/articles/history-electric-car

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_electric_vehicle

- https://www.caranddriver.com/features/g43480930/history-of-electric-cars/

- https://www.wired.com/2010/06/henry-ford-thomas-edison-ev/.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Motors_EV1.

- https://www.caranddriver.com/photos/g32944120/tested-1997-general-motors-ev1-gallery/.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uep5zOrsAEA.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/11/business/energy-environment/trump-republicans-electric-vehicles-automakers.html.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uep5zOrsAEA.